You probably don’t speak Old Norse. No-one does – it died out in the Middle Ages – but you’ve been using Old Norse words your whole life without knowing it. Ever been ‘angry’, boiled an ‘egg’ or baked a ‘cake’? All of these words began life as Old Norse, one of the many, many languages to have influenced English and given us the words we use every day. Many of our culinary terms are French, our nautical terms Dutch and our scientific terms Latin or Greek. ‘Shampoo’ comes from Hindi, ‘algebra’ from Arabic and ‘chocolate’ from Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs.

While English has absorbed words from all over the world, it has taken surprisingly few influences from its Celtic neighbours. There are always exceptions, however. In honour of St Patrick’s Day, here are ten English words of Irish origin and the stories behind them.

1. Banshee

In Irish folklore, a banshee is a female spirit whose cries herald the death of a family member. The word comes from a phonetic spelling of the Irish bean sídhe, meaning ‘woman of the hills’ or ‘woman of the fairies’.

The link between hills and fairies may seem hard to fathom until you consider the connection between Irish folklore and the Irish landscape. Ireland is littered with tumuli, earthen mounds that were built as burial sites, many of which date back to the neolithic era. Over time, these mounds became associated with the Sidhe, or fairy people.

The Sidhe were identified with the Tuatha Dé Danann, the gods of pre-Christian Ireland. According to legend, the Tuatha Dé Danann were defeated by the Milesians, semi-mythical settlers from Spain who are seen as the ancestors of all Gaelic Irish, and driven underground into the tumuli.

Although banshees are more part of Irish folklore than mythology, elements of their mythological roots can be found in the stories about them. For example, they will only haunt people with Gaelic (ie Milesian) ancestry – typically denoted by surnames beginning ‘O’ or ‘Mac’ – and not Irish people whose heritage is Saxon or Norman. Their practice of wailing to announce a death in the family, known as keening, is also associated with the Celtic goddess Brigid.

2. Craic

For a word that seems so quintessentially Irish, it comes as something of a shock to find that ‘craic’ is actually English. Broadly meaning ‘fun, enjoyment’ or referring to a good time, it comes from the Middle English ‘crak’, meaning ‘loud conversation, bragging talk’. In fact, the word has featured in Scottish and Northern English dialects for around five hundred years. Although it has a history in Ulster, a region with strong cultural links to Scotland, it was almost entirely unknown in the Republic of Ireland until the 1960s or 1970s.

Initially, the word was spelled ‘c-r-a-c-k’. The ‘c-r-a-i-c’ spelling was originally just an Irish translation of the English word (the Irish alphabet has no ‘k’), but became prominent among English speakers in the 1990s, much to the annoyance of some commentators.

In an article for The Irish Times, Donald Clarke bemoans the widespread adoption of this spelling, damning it as ‘bogus Irishness’ and seeing it as ‘a relic of the peculiar surge of confidence that energised the Irish experience in the 1990s’, a time when the economy was strong and national confidence was buoyed by success at the 1990 World Cup and the international popularity of Riverdance.

For the word’s critics, the rise of ‘craic’ represents a kind of commodified Irishness, a stereotype of the national character sold around the world along with Irish pubs and Shamrock hats. Nevertheless, the movement of a word from English to Irish and back to English again highlights the porousness of language’s borders and the speed with which a word can become freighted with cultural meaning.

3. Whiskey

In R. F. Kuang’s 2022 novel Babel, translation is a form of magic. Silver bars are imprinted on one side with an English word and on the other with its equivalent in another language. The gap between the two meanings – in effect, that which is lost in translation – is the source of power. In this world, the bar for ‘whiskey’ would be particularly welcomed by drinkers, as the word’s root, the Old Irish uisge beatha, literally means ‘water of life’, so it might well ameliorate the effects of a heavy drinking session.

Irish isn’t alone in associating alcohol with life. In fact, uisge beatha is a direct translation of the Latin aqua vitae, which also gives us the French eau de vie, better known to English speakers as brandy.

Although the invention of whiskey is claimed by both Ireland and Scotland, Ireland can claim a head start in the spirits war. The first reference to uisge beatha comes in 1170 and was made by Henry II, shortly after his invasion of Ireland. According to legend, however, the origins of Irish whiskey go back even further, lying with St Patrick, who is said to have introduced distilling to Ireland. Although it is difficult to prove this claim, the world’s oldest licensed distillery, Bushmills, is located in County Antrim, Northern Ireland.

4. Galore

While some of the words on this list have complex histories, the origins of ‘galore’ are fairly straightforward. First used in the 1670s, it derives from the Irish Gaelic phrase go leór, meaning ‘sufficiently’ or ‘enough’.

Galore is an example of a postpositive adjective, meaning that it appears after the noun it describes, as in the name of the Ealing Comedy Whisky Galore!. Such adjectives are rare in English and tend to sound old-fashioned, although they do appear in some phrases, such as ‘poet laureate’.

5. Phoney

The Oxford English Dictionary claims that the origin of the word ‘phoney’ is unknown, but there is an argument that it has its roots in Irish and gained its meaning via a notorious con trick.

‘Phoney’ may only have emerged as a slang term in late-nineteenth-century America, but the word ‘fawney’ goes back further. In Francis Grose’s 1785 book Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, a compilation of rude and slang terms, he describes the Fawney Rig as ‘a common fraud, thus practised: A fellow drops a brass ring, double gilt, which he picks up before the party meant to be cheated and to whom he disposes of it for less than its supposed, and ten times its real, value’.

In an article for The Irish Times, Frank McNally writes about falling prey to this exact con. Reflecting on the incident, he suggests a connection between the Fawney Rig (‘rig’ here means ‘a trick or swindle’) and the Irish word fainne, meaning ring.

6. Slogan

If you’ve ever felt besieged by contemporary marketing, you can take a grim satisfaction in knowing that the word ‘slogan’ has its origins in war. In both Irish and Scottish Gaelic, a sluagh-gharim was a battle cry, yelled by clans during their raids.

Prior to being adopted by advertisers and politicians, slogans were used in Scottish heraldry, appearing as family mottos above a crest or below a shield.

The modern meaning of the word dates back to 1704, when it was defined as ‘the distinctive note, phrase or cry of any person or body of persons’. At the time, the word was spelled ‘slughorn’. As well as possibly naming a teacher at Hogwarts, the word’s unusual spelling gave rise to a famous literary mistake. In Robert Browning’s 1855 poem Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came, the final stanza concludes:

I saw them and I knew them all. And yet

Dauntless the slug-horn to my lips I set,

And blew.

Browning clearly didn’t know his etymology and assumed that a slug-horn was an actual musical instrument. (To find out about another – this time hilariously rude – misunderstanding in Browning’s poetry, see Erica McAlpine’s article ‘Reading Gone Awry’.)

7. Tory

It is easy to assume that ‘Tory’ must somehow be an abbreviation of ‘Conservative’, but this nickname of one of Britain’s main political parties has surprising Irish roots. Even more surprisingly, it predates the founding of the Conservative Party by several centuries.

The Online Etymology Dictionary traces Tory back to 1566, at which time it meant ‘outlaw’, deriving from the Irish toruighe, meaning ‘plunderer’. During the seventeenth century, it acquired a more specific meaning, becoming a derogatory term for dispossessed Irish Catholics, some of whom became outlaws in order to survive.

It first gained a political meaning in a British context between 1679 and 1681, during the Exclusion Crisis. This was a dispute within Parliament concerning the succession of Charles II. Tories argued that, as next in line to the throne, Charles’s younger brother, James, should succeed him as king, while the Whigs argued that, as a Catholic, he should be excluded from the line of succession. The Tories ultimately won the argument and James became king in 1685.

Despite its initial association with Catholicism, by the nineteenth century, the term had become more associated with Anglicanism, and Tories were characterised by their monarchist leanings and strong sense of patriotism. The modern Conservative Party emerged in the 1830s under Robert Peel, but the term Tory continued to be used as a synonym.

Although the term remains popular, it hasn’t always been embraced by Conservatives themselves. In 2005, the party’s head of broadcasting emailed TV bosses to ask them to refer to them as Conservatives rather than Tories.

8. Taoiseach

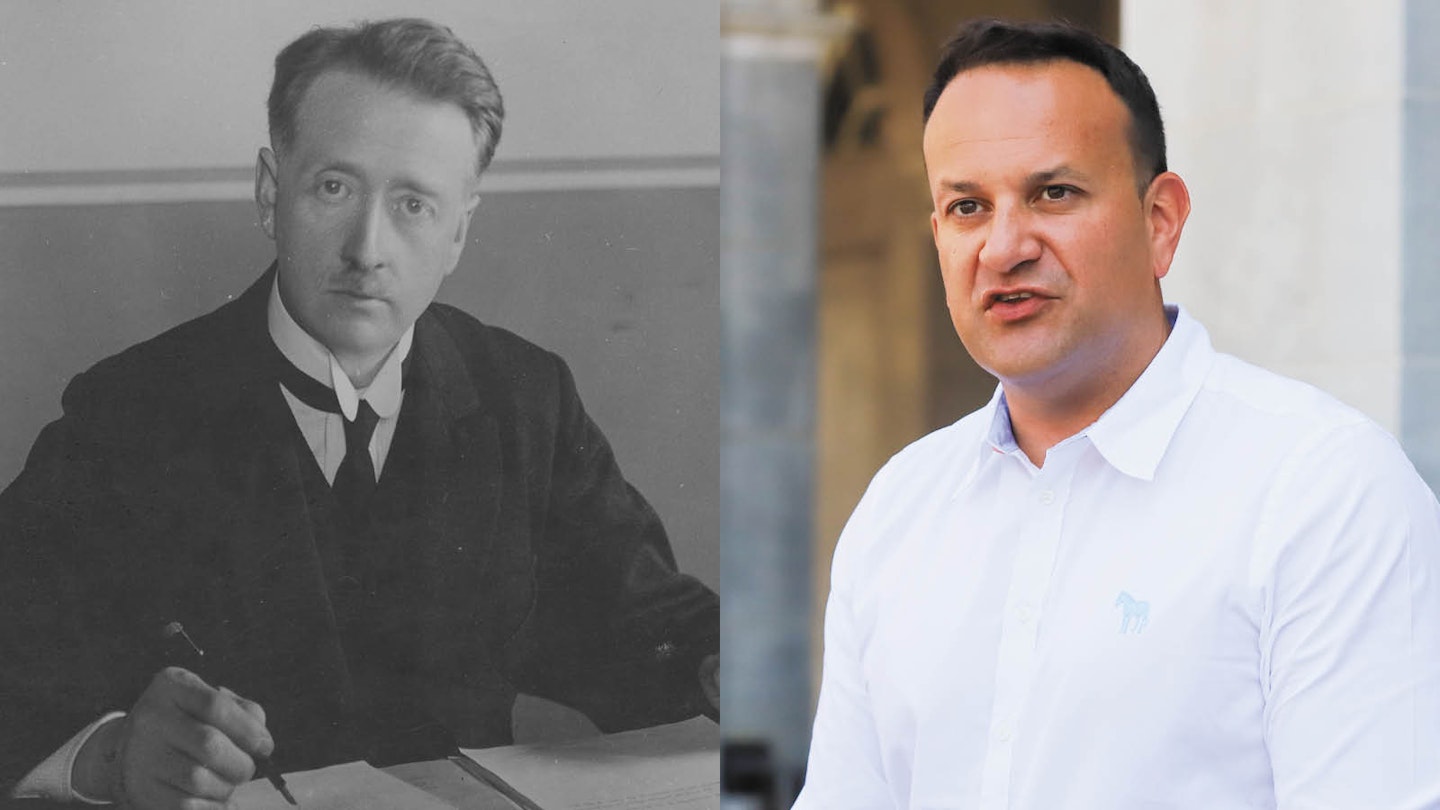

Turning now to Irish politics, ‘Taoiseach’ (pronounced a bit like ‘tea-shuck’) is the name given to Ireland’s prime minister. The word comes from the Irish for ‘chieftain’ or ‘leader’ and was first used in 1937, when Ireland adopted its current constitution. Usually the leader of the largest political party, the Taoiseach is nominated by members of the Irish parliament, known as the Dáil Eireann, and formally appointed by the President.

The adoption of the term Taoiseach wasn’t without controversy, however. Opposition politician Frank MacDermott opposed using the word on the grounds that ‘it would be pronounced wrongly by 99 percent of the population’, and instead advocated for the English ‘prime minister’.

Although Irish has been the official language of Ireland since independence in 1922, it is not widely spoken. In 1936, just under a quarter of the Irish population could speak it, with the figure being highest in the western province of Connaught.

Today, the Irish language is classed as ‘Definitely Endangered’ by UNESCO. According to the most recent census only 71,968 people speak it on a daily basis.

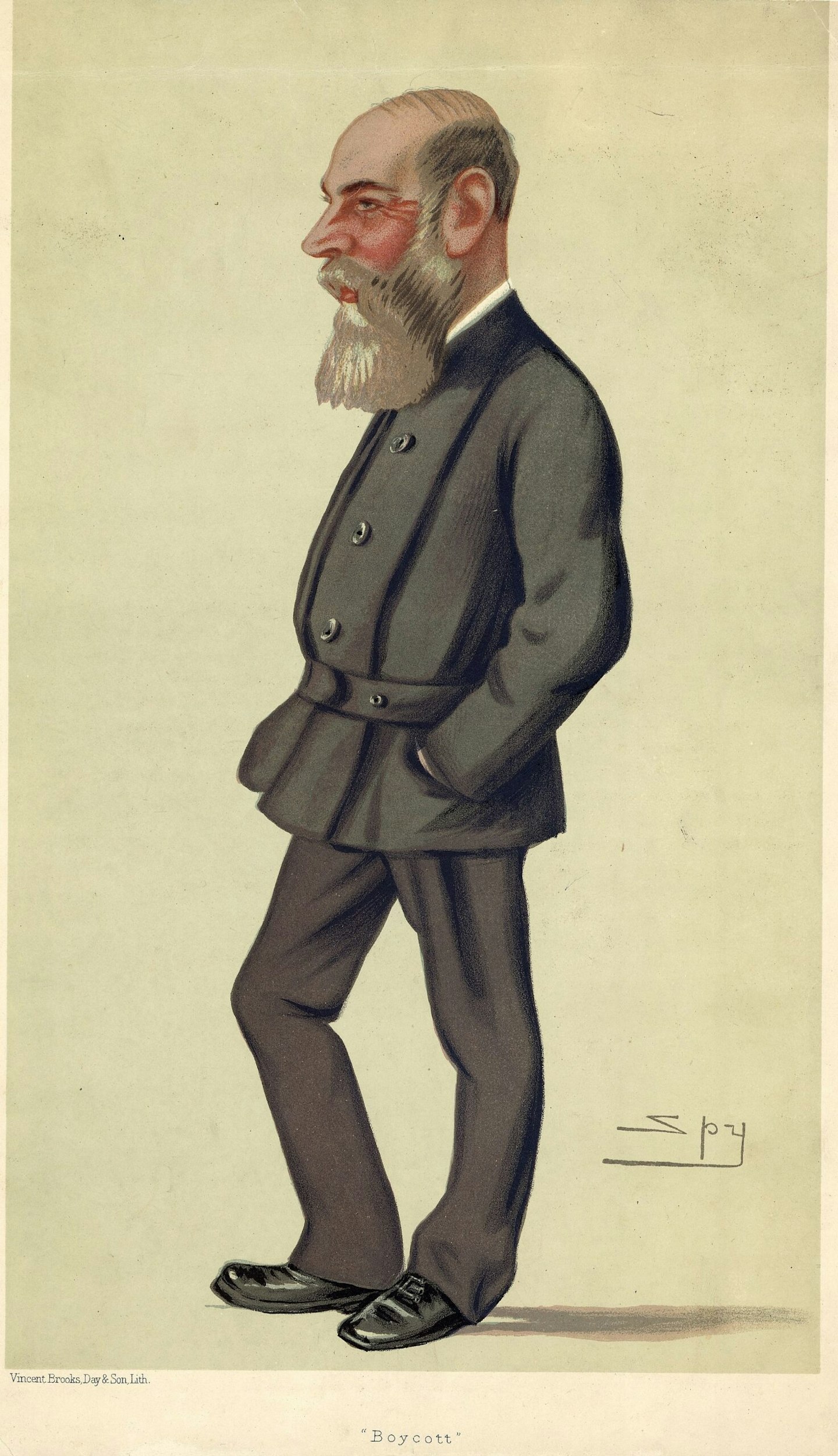

9. Boycott

Unlike most of the other words on this list, ‘Boycott’ doesn’t have Celtic roots. In fact, it comes from an English surname, itself derived from place names in Shropshire and Buckinghamshire that mean ‘Servant cottage’. The use of the name as a verb, however, originates in the turbulent politics of nineteenth-century Ireland.

Captain Charles Cunningham Boycott was born in Norfolk in 1832. At the age of 18, he joined the army, despite having failed his military exams. Soon after this, he moved to Ireland, where his regiment was based, and remained there after leaving the military. He married and became a farmer.

For much of this time, he lived on the beautiful, but remote, Achill Island, located off Ireland’s west coast. In 1872, however, he took up an offer by Lord Erne to become a land agent for his estate in Lough Mask, County Mayo, a job that involved looking after the land and collecting tenants’ rents.

During the late 1870s, an economic downturn badly affected Irish agriculture, leading to sharp rent increases and mass evictions. In October 1879, the Irish National Land League was established to organise tenant farmers against their landlords, leading to a period of unrest across the Irish countryside known as the Land War.

When Boycott began evicting tenants, the League urged his employees to withdraw their labour and he found himself ostracised by the local community. Boycott wrote to The Times to complain about his treatment and became a major cause célèbre, leading to volunteers travelling down from Ulster to help bring in his harvest. The sheer number of volunteers, however, proved counterproductive, as their presence risked fuelling sectarian tensions and the cost of saving the crops far exceeded their value. On 27 November 1880, Boycott left County Mayo and returned to England, selling his property in Ireland six years later.

Boycott may have left Ireland, but his time there had already made its mark on the English language. By the end of 1880, his name had become synonymous with ostracisation and was widely used in the newspapers. According to the American journalist James Redpath, the term ‘to boycott’ was coined by Father John O’Malley, a curate who was one of the leaders of the Land League’s campaign in Lough Mask. He felt that the peasantry wouldn’t know the meaning of the word ‘ostracism’, so adopted Boycott’s name instead.

10. Hooligan

Like boycott, ‘hooligan’ is a word that comes from a name. It is widely agreed that it derives from a variant of the Irish surname Houlihan and entered the English language sometime in the 1890s, but the exact origins of the term are uncertain.

The Online Etymology Dictionary traces the word’s origin to the stage, noting that Hooligan was used as ‘a characteristic comic Irish name in music hall songs and newspapers of the 1880s and ’90s’.

The earliest reference to hooligan meaning delinquent, however, comes from 1894, in a Daily News article about a case at Southwark Police Court. It describes 19-year-old Charles Clarke as ‘the king of a gang of youths known as the ‘Hooligan boys’’. Although the term hooligan dropped out of use for a couple of years, it re-emerged in 1898, when a member of the Hooligan gang was charged with the murder of Henry Mappin in Lambeth.

Although these references are to groups of people, rather than individuals, Clarence Rook’s 1899 novel The Hooligan Nights tells the story of one particular hooligan. According to Rook, Patrick Hooligan ‘walked to and fro among his fellow-men, robbing them and occasionally bashing them’. Young Alf, another character in the book, describes Hooligan’s ‘regular business’ as ‘giving mugs and other barmy sots the push out of pubs when their old swank got a bit too thick’. Hooligan’s criminal activities eventually catch up with him, however, and he finds himself jailed for the murder of a policeman.

Whatever the precise origin of the word, it was quickly taken up by the media, with ‘hooligan gang’ and ‘gang of hooligans’ replacing the more traditional ‘gang of ruffians’ in newspaper articles. Arthur Conan Doyle and H. G. Wells are among the writers who used the term in novels and stories written in the 1900s.

By the 1970s, the term began to refer more specifically to violent football fans in the UK, while, in the USSR, the word khuligan was used to denigrate both illegal drinkers and political dissidents, showing the extent to which the word has evolved from its origins in nineteenth-century London.