Rian Johnson’s hit 2022 film Glass Onion is full of celebrity cameos, but perhaps the most impressive is a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moment early on. Bored during lockdown, southern supersleuth Benoit Blanc, played by Daniel Craig, is playing the online game Among Us with some friends via Zoom. These friends just happen to be basketball legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, actress Natasha Lyonne, star of stage and screen Angela Lansbury and famed musical composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim.

Given Johnson’s well-attested passion for whodunnits, the fact that several of these have a clear link to murder mysteries stands out. For example, Angela Lansbury spent over a decade as the mystery-solving novelist Jessica Fletcher in Murder, She Wrote, while Natasha Lyonne would go on to play the lead role in Johnson’s 2023 detective series Poker Face.

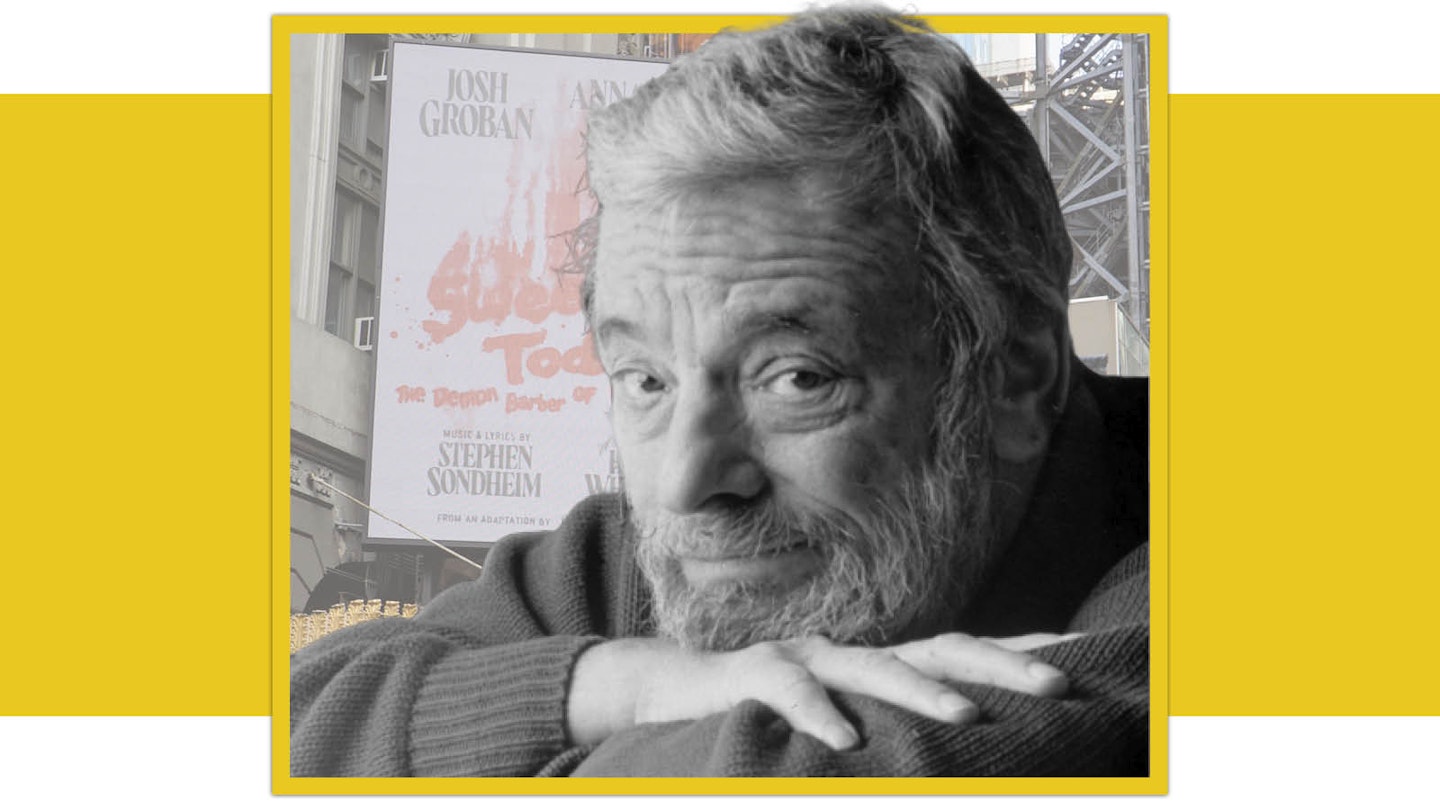

At first glance, the inclusion of Stephen Sondheim seems a little bit more surprising, but, while Sondheim may be best-known for his career in musical theatre, writing the music and lyrics to classics including Sunday in the Park with George, Sweeney Todd and Into the Woods, he also fits into the world of the murder mystery.

In fact, of the four stars featured in the cameo, Sondheim had by far the closest connection to Glass Onion, via his only screenwriting credit, 1973’s The Last of Sheila, which he co-wrote with Anthony Perkins (a.k.a. Norman Bates in Psycho). Johnson has not only praised The Last of Sheila as having ‘one of the all-time great ‘70s casts’, but also cited it as a direct influence on Glass Onion. With its Mediterranean setting, intricate plot and A-list cast of obnoxious – but fun to watch – rich people, it’s not hard to see why.

In The Last of Sheila, film producer Clinton Greene, played by James Coburn, invites a group of Hollywood friends for a week on his yacht in the South of France. They are there ostensibly to make a film about his late wife, Sheila, who died a year before in a still-unsolved hit-and-run incident, but they’re also there to play what Clinton calls ‘The Sheila Greene Memorial Gossip Game’. Everyone is given a card containing a secret; each night, they will dock in a different port, where they will be tasked with solving a series of clues to uncover one another’s secrets. As the game goes on, however, it quickly becomes clear that these secrets aren’t quite as fictional as they first appear. From then on, things get steadily more sinister…

The Last of Sheila is a carefully crafted, Agatha Christie style mystery in which every clue and line of dialogue, no matter how apparently throwaway, turns out to be a piece of the puzzle. It also has a sometimes twisted, cynical sense of humour – familiar, perhaps, to fans of Sondheim’s musicals – that gives it a much more adult atmosphere than most other murder mysteries. The Last of Sheila may not be as well-known as other films of its era, but it is well-worth seeking out for its dark, enjoyably bitter take on a traditionally cosy genre.

While The Last of Sheila may have been Sondheim’s only screenwriting credit, his passion for puzzles and mysteries extended well beyond it. In fact, the film has its roots in Sondheim’s own pastimes. During the 1960s and ‘70s, he hosted real-life murder mystery games for his friends, including Anthony Perkins, Anthony Shaffer (a screenwriter whose own passion for puzzles is made clear in his scripts for Murder on the Orient Express, Death on the Nile and Sleuth) and Herbert Ross, who would go on to direct The Last of Sheila.

Perhaps one of the most elaborate and memorable of Sondheim’s murder mysteries, this time designed with Perkins’ help, was a giant treasure hunt through New York. According to Games Magazine, ‘one of the stops was a Manhattan apartment where a kindly old woman served tea and cakes to the visiting hunters. “If you ate the cakes,” Sondheim remembers, “you destroyed the clue. It was written in the icing – part of it on each of the five cakes the old lady served.”’

Up to the challenge

Murder mysteries were just one aspect of Sondheim’s connection to the world of puzzles, however. Sondheim described himself as having a ‘puzzles mind’ and loved the fact that, no matter how challenging a puzzle, there’s always a solution, a parallel he also saw in murder mysteries. It’s therefore unsurprising that he was such a passionate enthusiast for crosswords. In fact, Sondheim is often credited with introducing the cryptic crossword to America.

Interestingly, Sondheim’s passion for puzzles and musical theatre came, quite literally, from the same place. As a young boy, growing up in Pennsylvania, he befriended the son of Oscar Hammerstein, the acclaimed lyricist of musicals including Oklahoma!, South Pacific and The Sound of Music, and, through him, got to know his father.

Hammerstein acted as a mentor to the young Sondheim, teaching him about song writing. He also introduced him to the Puns and Anagrams puzzles in The New York Times, created by crossword pioneer Margaret Farrar. At age 14, he submitted his own puzzle to the newspaper. The reply he received was encouraging: ‘We’re very impressed, it’s very perspicacious’. The budding puzzler had to look up this last word.

While Sondheim may have been passionate about puzzles, this passion was not shared equally for all types. In fact, he was highly vocal about his hatred for the type of crossword then most common in America, which he described as a ‘mechanical test of tirelessly esoteric knowledge’. By contrast, the appeal of the cryptic crossword was almost literary, each clue a mystery story in miniature. In his article ‘How to Do a Real Crossword Puzzle’, published in New York Magazine on 8 April 1968, Sondheim describes how, ‘In the best puzzles, styles of clue-writing are distinctive, revealing special pockets of interest and small mannerisms, as in any prose style’.

For Sondheim, the best crosswords were to be found in Britain. He was particularly fond of The Listener, the magazine set up by the BBC in 1929 and famed for the difficulty of its cryptic crosswords.

A man on a mission

In 1968, Sondheim brought this style of crossword to the USA, regularly publishing puzzles in New York Magazine, until the rigours of working on the musical Company became too much and he was forced to stop contributing in 1969.

Although Sondheim’s article on ‘how to do a real crossword puzzle’ provided an introduction to cryptics, he made few concessions to American inexperience. In his book The Crossword Century, Alan Connor notes that trying ‘to introduce newcomers to the delights of a British cryptic with Listener-style clues is a bit like persuading people to take a pleasurable healthy stroll on the weekends by dropping them blindfolded into the Borneo jungle equipped with a butter knife for hacking through the undergrowth’. Even if Connor is exaggerating for comic effect, there’s no denying that Sondheim’s puzzles are hard.

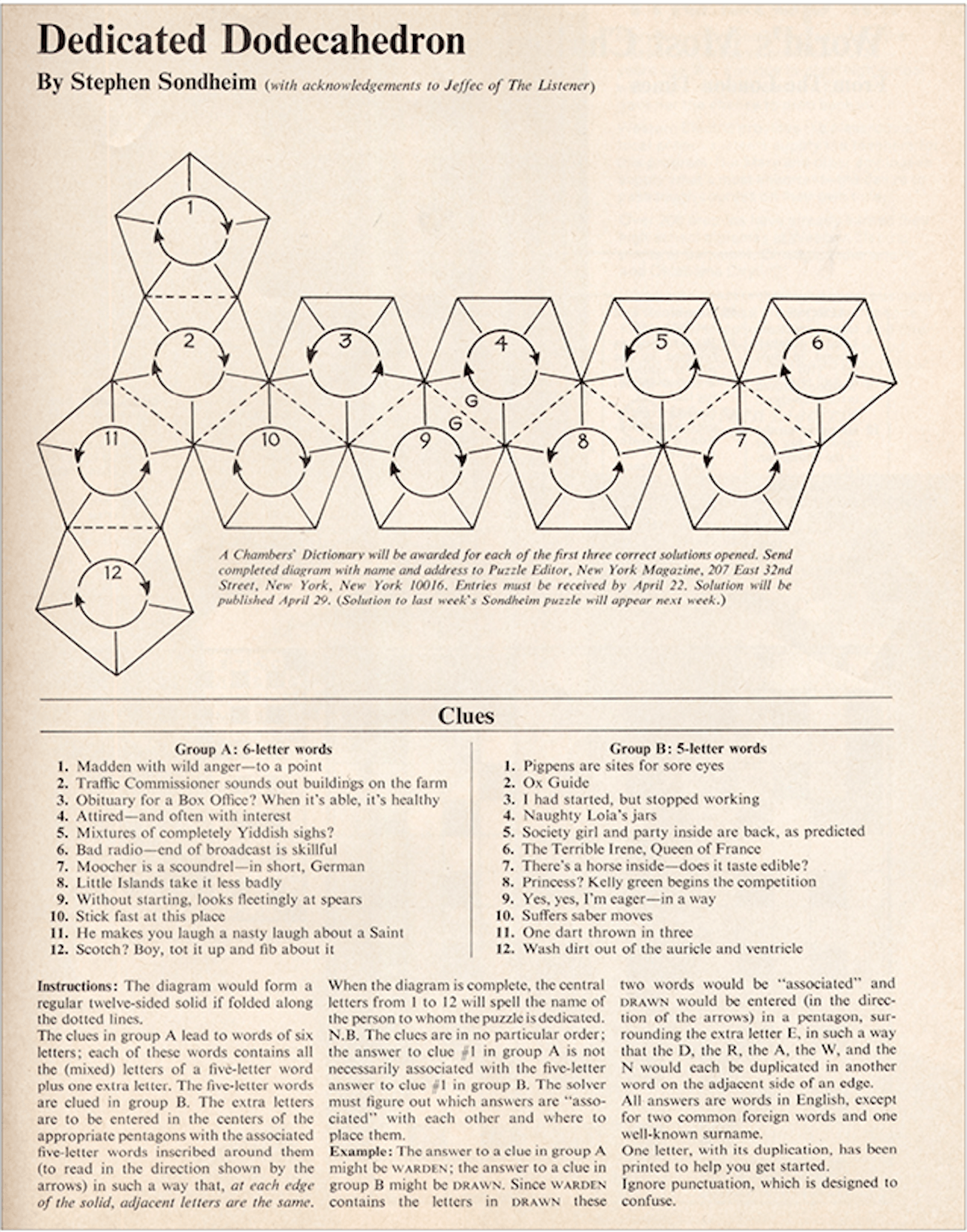

Take the Dedicated Dodecahedron, for instance. This puzzle, which Sondheim seems to have invented, contains 24 clues, 12 of which give six-letter answers and 12 of which give five-letter answers. Each of the six-letter answers is an anagram of one of the five-letter answers, with one letter added. These clues are accompanied by a complicated-looking geometric diagram, a series of pentagons which can be folded together to make a dodecahedron. Each pentagon contains a central circle, into which solvers must put the additional letter from each pair of clues, while placing the remaining letters around the edge in such a way that two or three of them are shared between pentagons. When completed, the central letters add together to give the name of the person to whom the puzzle is dedicated.

With all these different steps, it’s no surprise that the instructions take up almost as much space as the clues. That said, taking these different elements individually makes the puzzle much more approachable. In fact, readers of Take a Crossword and Take a Puzzle will notice elements of the Brickworks and Octogram puzzles in Sondheim’s dodecahedron. Five-letter clues such as ‘Pingpens are sites for sore eyes’ (STYES) and ‘Princess? Kelly green begins the competition’ (GRACE) will also be solvable even by cryptic crossword novices. Despite the fiendishness of his puzzles, Sondheim goes out of his way to be fair. In fact, he is credited with introducing ‘square-dealing’, a standardised way of indicating the kind of wordplay required in a clue, to the USA. He even includes this helpful note in the instructions to his puzzles: ‘Ignore punctuation, which is designed to confuse’.

Tying up loose ends

Sondheim may now be best-remembered for his huge contribution to the world of musicals, but his effect on crosswords was equally significant, inspiring a whole generation of American crossword setters, including husband-and-wife duo Emily Cox and Henry Rathvon, former setters for The Atlantic and The Wall Street Journal. His love of crosswords even cross-pollinated back into the world of musical theatre, as he got Leonard Bernstein hooked on cryptics while writing West Side Story.

When Sondheim was asked about the connection between compiling crosswords and writing musicals, he generally deferred, emphasising his view that art is about ‘making order out of chaos’. There is, however, perhaps a greater connection. In his musicals, Sondheim recognised that puzzles of the heart were not always solvable; crosswords and murder mysteries therefore acted as a counterbalance. In life, puzzles may never be solved, but, on paper, they always can.